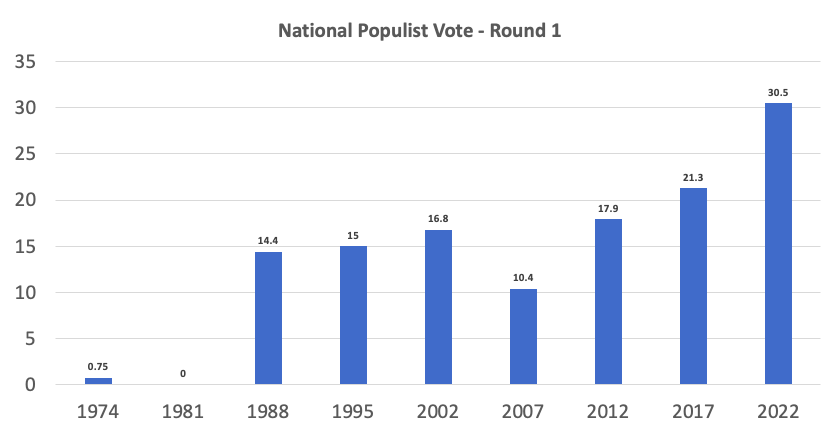

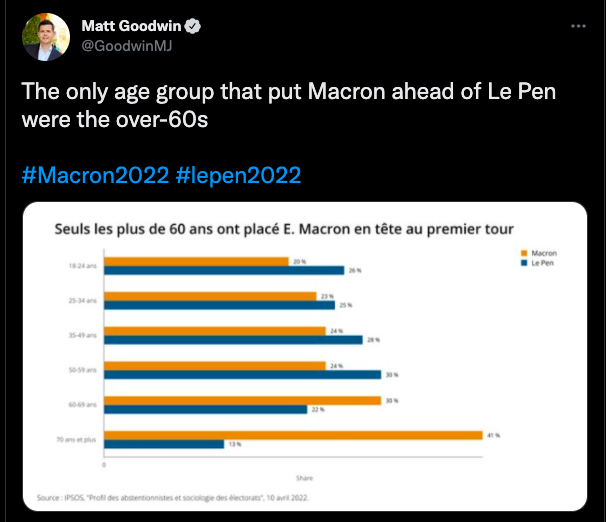

| Welcome to the politics memo of Matthew Goodwin, for busy people. Can Marine Le Pen win? It’s a question I’ve been asked a lot at recent events in Brussels, Westminster and the City of London. Here’s a piece I wrote for my friends at UnHerd with some additional analysis for subscribers. Whatever happens in the second round of the French election, Marine Le Pen can in some respects already claim victory. If the polls are correct, as they were in round one, then Le Pen looks set to win somewhere around 40-45% of the vote. While she will likely fail to win the presidency she will be able to saviour another prize: the knowledge that she has forever broken the mould of French politics.We can get a sense of the scale of what is unfolding in France by stepping back to look at the evolution of the national populist vote since 1974. The story is one of stubbornly persistent growth: 0.75% in the first round in 1974, 15% in 1995, 18% in 2012, over 21% in 2017, and, now, to over 23%. But even that is only a partial picture. Combine Le Pen’s vote with Eric Zemmour’s and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan’s and the picture is more dramatic. Together, earlier this month, they polled more than 32% — ten points more than what Marine Le Pen won five years ago and nearly double what she received a decade ago. Remarkably, they received a higher share of the vote than all of France’s Left-wing parties combined. This gives us good evidence to suggest that national populism is now fully consolidated on the landscape of French politics and may well be about to score further against at the legislative elections in June.  In the next round, on Sunday, Marine Le Pen is also forecast to surpass the 33% she won in 2017 by 13 points — more than double the 17% her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, polled in the final round 20 years ago. Such is Le Pen’s progress that were she to replicate her father’s vote, which stunned the world, then it would be seen as a colossal failure.Nor is she anywhere near as toxic as he once was. According to one Ifop survey last week, almost half the French, 46%, said they trusted Le Pen to defend democratic values (versus 50% for Macron). Other surveys during this campaign have produced results that are just as striking, including one which found voters were more likely to see Le Pen, over Macron, as « sincere », « capable of changing the country », and « courageous » (though much larger numbers also saw her gains as « worrying »). The key point in all this is that many people simply no longer view the Le Pen brand as being as toxic as earlier generations did.None of this was supposed to happen. One fashionable narrative during the pandemic was that Covid-19 would kill off populism as people flocked back to the old parties, the technocrats, and the experts. Take a report by the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge, which concluded that support for populism had “collapsed” since the Covid outbreak, due to a “technocratic shift” in global politics. “Electoral support for populist parties,” wrote the lead author, Dr Roberto Foa, “has collapsed around the world in a way we don’t see for more mainstream politicians. There is strong evidence that the pandemic has severely blunted the rise of populism.”But the elections in France, and elsewhere, point in the opposite direction. In the first round, two-thirds of the French just voted for anti-establishment candidates outside of the incumbent president and the two mainstream Gaullist and socialist traditions which have dominated post-war France. Combined, support for the French Gaullists and the socialists collapsed from 54% in the late Eighties to just 6% today. Over the last half century, the French socialists — once the pre-eminent Left-wing party in Europe — have fallen from over 40% to just 1.7%. They are, in short, almost extinct. It is Marine Le Pen, not the Socialists, who can claim with a straight face to be the main working-class party in French politics. In the second round polls, while middle-class professionals break for Macron over Le Pen by a ratio of 63% to 37%, workers break for Le Pen over Macron by a ratio of 66% to 34%. .  Nor, for that matter, do other populists appear to be struggling. As Roger Eatwell and I argued in our book, National Populism, while the rise of these parties has raised worrying and important questions about the future of liberal democracy, they have also now become a permanent feature on the political landscape. In Germany last year, for instance, the Alternative for Germany’s share of the national vote fell by just 2 points to 10%, leaving it with 83 seats in the Bundestag (something that would have been considered unthinkable only a decade ago). In the Netherlands, while support for Geert Wilders fell slightly, support for Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy increased, putting them both on 16% — an increase on their result four years earlier. In Norway, the Progress Party fell nearly four points to 12% but further south, in Portugal, the new Chega! (Enough!) Movement just entered parliament for the first time with 7% of the vote and their first twelve seats. In the Czech Republic, Andrej Babiš recently lost 2 points but still polled 27% while, last month, in Spain’s Castile and León region, the Vox movement won its best ever result with 17.6%. Then, last month in Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz were comfortably re-elected with over 54% of the national vote.Further afield, too, 2022 looks set to reaffirm the existence of national populism, not push it into retreat. In November, at the US midterms, Trumpian Republicanism looks set to have a strong return. Joe Biden’s approval rating is now just 35% – lower than the approval rating for every other president at the same point in the cycle, with only one exception: Donald Trump. Today, nearly two-thirds of all voters say America is “on the wrong track” while the first polls for the 2024 presidential election put Trump four-points clear of Biden.Of course, there are examples of populists falling off the rails, such as Bolsonaro in Brazil, who is routinely trailing the Left in the polls. But when seen as a whole, and especially in Europe, the idea of populism being on the ropes is wishful thinking.The notion that Covid would kill off populism isn’t the only narrative Le Pen has overturned. Contrary to the idea, fashionable among liberal progressives, that populist voters would die out, Le Pen’s vote points to a new populist wave in Europe. In the first round of the presidential election, she polled ahead of Macron among everybody under 60 years old. The only people who flocked to Macron’s liberal centrism were the over-60s.Look at the polls for the second round, too, and much of Le Pen’s support comes not from nostalgic pensioners who yearn to return to the Fifties but younger voters, especially young women. Typically aged 18-34 years old, they work in skilled, semi-skilled, or unskilled jobs in the new working class — in sales and services — where they have found themselves on the wrong side of globalisation, automation, immigration, and a new cost of living crisis.Ever since the Nineties, the Le Pen dynasty has been most popular among blue-collar male workers. But more recently it has appealed far more to socially secure workers on lower-middle incomes who are squeezed between liberal professionals and the unemployed. They are the voters, in other words, who are especially likely to feel they have something to lose, whether from downward social mobility, rising immigration, neglectful elites, or rampant globalisation, much like the skilled and semi-skilled workers who abandoned the Labour Party for Boris Johnson.Ask Le Pen’s voters to name their top concerns and they are certainly more likely than the average voter to flag their intense worries over immigration, security, and, further down the list, the need to control Islamist terrorism. But their top concern, by far, has little to do with cultural issues: it is their declining “purchasing power”. They are not only united by the sense they are losing out socially, being pushed further down the social ladder behind the new graduate elite, immigrants and minorities — they cannot even afford to tread water and stay where they are.  Amid spiralling inflation and energy costs, Le Pen is appealing to French people who were typically born between 1988 and 2004, who have no memory of her father’s toxic campaigns, who have grown up in a world where populism is entirely normal, not an aberration, whose young lives were defined first by the global financial crisis and then by the Covid lockdowns, and who have never known a thriving, secure, growing French economy with low rates of unemployment. Why would they trust the old politics?Many have spent their adolescence amid high youth unemployment rates of at least 20%, low rates of economic growth and, on top of that, some of the worst Islamist atrocities in Europe. Le Pen has deliberately tried to woo these voters in a way her father never could. Look at her policies and you will find the expected call for a national referendum on “uncontrolled immigration”, a rather vague pledge to « eradicate » Islamist ideology and its networks from French territory, to toughen up sentences for criminals and reinstate border controls and weaken France’s relationship with the EU and NATO.But you will also find calls to slash VAT, raise wages, renationalise motorways, and a range of measures for younger people — monthly training vouchers for apprentices, the removal of all workers under 30 years old from income tax, the removal of corporation tax for entrepreneurs under 30, the building of 100,000 new accommodation units for students, and 0% loans for young families to try and stop them moving abroad and to encourage them to have more children.This effort to connect with a new generation of French voters is clearly working. Already, ten years ago, in 2012, the French political scientist Nonna Mayer observed how Marine Le Pen had successfully closed the male-heavy “gender gap” which had characterised not just her father’s vote but support for other populists across Europe. Unlike her father, a former paratrooper who had shown little genuine interest in “de-demonising” his party and was, at times, anti-Semitic, Marine Le Pen made serious inroads not only among women but also LGBT communities who often perceive their hard-won rights are under threat from Islamism.It is this generation of voters, she hopes, who will continue to push her forward, irrespective of what happens next Sunday, and perhaps in the form of some kind of broader populist alliance at the legislative elections in June. Le Pen may not capture the Élysée Palace this time — but the question, increasingly, is when, not if.  Thanks to those who invited me along to speak at various events in recent weeks. It is good to see the event space getting busy again after a dismal two years. Contact Matt Goodwin’s Memo is sent fortnightly to 7,800 analysts, decision-makers, leaders & citizens. Feel free to share. Feel free to subscribe . Copyright © 2021 Matt Goodwin’s Memo. All rights reserved. |