By Matthew J.Goodwin <m.j.goodwin@kent.ac.uk>

Fri, 9 Apr at 09:00, 2021

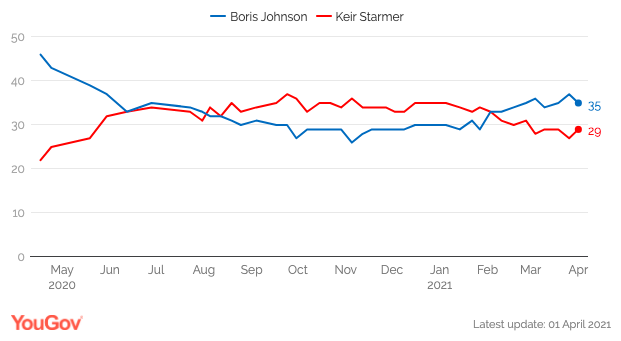

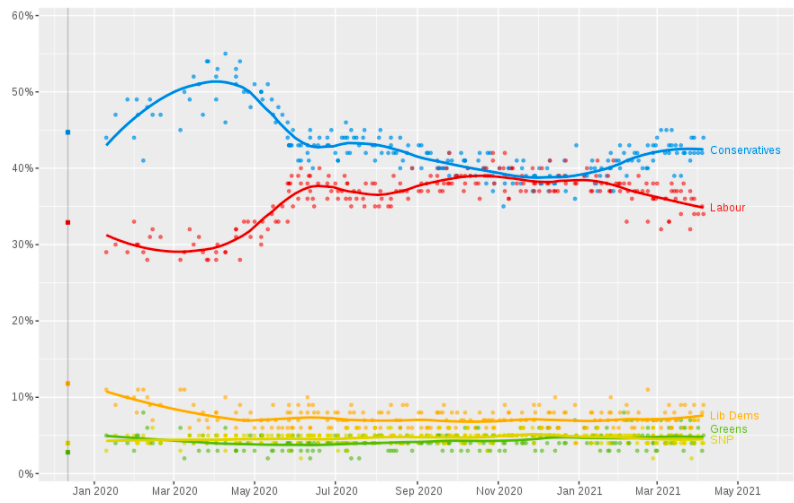

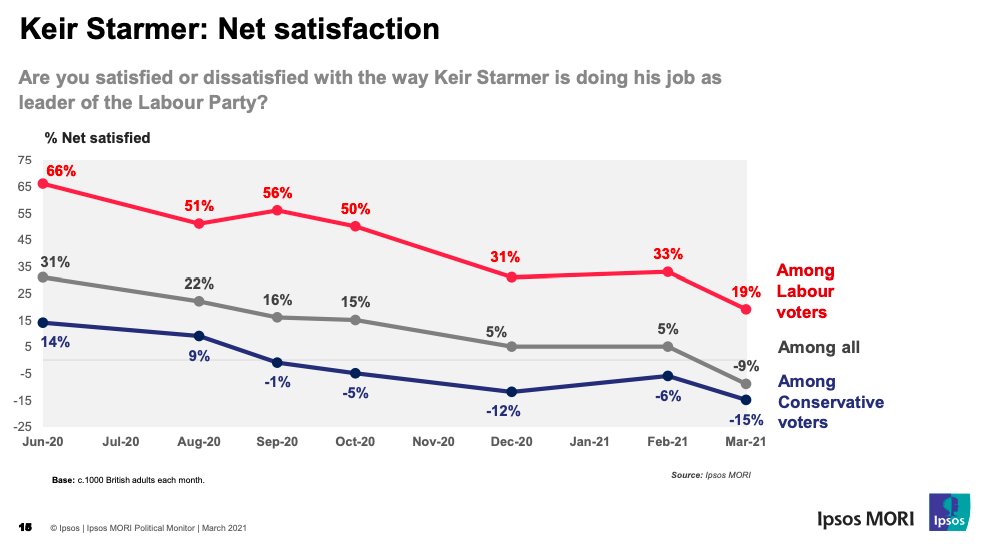

| [Some of this draws on recent talks at the Council on Foreign Relations, UK In a Changing Europe, Withers LLP and Atticus Communications.] There are some leaders of the opposition who you always knew, in your heart of hearts, would never become Prime Minister. Michael Foot, William Hague and Iain Duncan Smith are the more obvious examples. Keir Starmer might soon be another. Starmer, in his defence, inherited a sinking ship. He was handed the lowest number of Labour seats since 1935, a bitterly divided party and a Labour brand that even today remains thoroughly discredited among a large swathe of the country. Many of these problems had been building for decades. Labour’s fracture with the working class, its loss of credibility on crunch issues like the economy and growing dependency on social liberals who tend to congregate in the big cities and university towns where Labour no longer needs votes have all been a long time coming. This is why any recovery — if such a recovery is even possible — will be generational rather than cyclical. There is no doubt that Keir Starmer has made a good start. Over the past year, Labour has picked low-hanging fruit, winning back voters repelled by Corbyn. When Starmer took over his party was languishing on 28% and some 22-points behind the Conservatives; today, it is averaging 35% and trails by 8. But more recently this recovery has stalled, as can be seen in the chart below. Amid the successful rollout of the vaccines it is now the Conservatives who are pulling ahead. Of the last 50 polls, Boris Johnson and his party have led in 49. [Refer Image 1 below] How much of Labour’s improvement is down to Starmer also remains unclear. While his supporters point to his strong leadership ratings relative to Corbyn, the fact remains that even today Starmer’s “net satisfaction” score still lags well behind Boris Johnson — while 33% of voters are satisfied with him, 42% are not. And when people are asked who would make the “best Prime Minister”, Boris Johnson still leads comfortably on 37%. His nearest rival is not Starmer but ‘Not Sure’. The Labour leader is trailing in third, ten points adrift from the man who has been in power for a year and is criticised by much of the media on a daily basis. There are, of course, many who argue that Covid-19 dealt Starmer an unlucky hand. But critics might argue that it is precisely during moments of crisis, when the glare of attention is strongest, that leaders are made. It won’t be lost on Starmer’s team that it is precisely at the same time as the entire country has been sat at home, watching the news and paying attention to politics, that Starmer’s ratings have been falling. To put it simply, the more people have seen, the less impressed they have been. Starmerites might respond that his ratings are better than Mr Corbyn’s. This is true but we should remember that Michael Howard’s ratings were better than Iain Duncan Smith’s. Yet In the end, neither saw power. And it appears that the British people can sense that, too. More than half of them told YouGov last week that they simply do not see Keir Starmer as a prime minister in waiting. This is a problem. [Refer Image 2 below] And even if you put the question of leadership to one side, there remains little evidence that Labour is dealing with the deep-rooted structural problems that will make it very impossible for the party to win the next election. To do so would require a swing close to what Tony Blair and New Labour achieved in 1997 – with a leader who is nowhere near as popular as Blair was and a party that is nowhere near as popular as it needs to be outside of London and the university towns. Here is one fact to keep in mind; Labour has not won the popular vote in England since 2001 yet it is in England where the party needs to make up most ground. Today, Labour leads by 16-points in London -which it already controls- but trails the Conservatives by 26-points across the rest of southern England. In other words, Labour is stacking votes where it does not need them while failing to win votes were it desperately needs them. The broader realignment of British politics is reflected in the fact that while Labour’s Sadiq Khan’s will enjoy an easy victory at the London mayoral election next month, Labour will simultaneously struggle to hold its historic blue-collar fiefdom of Hartlepool. This reflects how Britain’s new political geography, the first-past-the-post system and earlier Labour leaders have made life harder than it ought to be for Starmer. Over the past two decades, the Left essentially walked into the casino of British politics and put all of its chips behind social liberals whose support is concentrated in liberal enclaves rather than spread across the country. The cost of this strategy was not only reflected in the collapse of the Red Wall but is also visible in the polls today. Ask the working class who should lead Britain and they give Boris Johnson a 19-point lead. Starmer might win a few more seats around London, but he should remember that there are many more Red Wall seats that could yet fall. The assault on the Red Wall might just be starting. [Refer Image 3 below] This reflects a broader point. At the heart of recent political commentary has rested one big assumption – that once Brexit was over and done with life would return to the traditional “Left versus Right” fault line that governed politics during the twentieth century. We would get back to debating the economic issues that play to Labour’s strengths and that would clear the path for the party to repair its relationship with workers and return to power. But I was never convinced. For a start, this narrative completely ignores the extent to which the Conservatives have now also leaned left on the economy, variously promising to “level-up” the most regionally imbalanced nation in the industrialised world while moving institutions, civil servants and banks into northern England. This stuff matters -it will give the Conservatives a strong narrative at the next election. The assumption that we are returning to the old world also underplays the extent to which cultural debates remain prominent in national life — as reflected in our intensifying debates over ‘cancel culture’, freedom of speech, the Royal Family and racism in British society. Boris Johnson is still holding a much more ‘aligned’ electorate than Starmer -while close to 70 per cent of Britain’s Leavers are with the Conservatives only 50 per cent of Remainers are with Labour. Put another way, Labour has still not fixed one of the big problems that ultimately cost it the election in 2019 -its far more fragmented electorate. These problems are also being reinforced by the cultural isolation of many Labour MPs and activists, who as much research has shown hold a very different outlook on these issues than the average person. They are far more convinced that racism is endemic in British society, are far more focused on tackling historic injustices and are, put simply, far more socially liberal. There is nothing wrong with these views. It is just that they are often very far apart from the worldview of the average person. Every day that progressive activists are in the media screaming about racist Britain is, ultimately, a good day for Boris Johnson. As Ronald Reagan reminded Jimmy Carter, nobody wants to be told over and over again what is wrong with their country and people. Put all of this together and you begin to see why it will be extremely difficult if not impossible for Starmer to chart a path to Number 10 Downing Street. While he might have steadied the ship, many (big) holes remain clearly visible and water is still gushing out – Labour’s broken bond with the working-class, its lack of economic competency in the eyes of voters, the cultural isolation of its MPs from the average voter and radical left activists who are cheered on in seats that Labour already holds but alienate people in seats that Labour actually needs to win. In year two, these are the areas where Starmer will need to act. Unless he does, he might find himself going down in the history books as the Labour Party’s Michael Howard -the man who brought stability but ultimately failed to win power. Best wishes Matt Goodwin Twitter – Website – SpeakingCopyright © *2019* *Matthew Goodwin*, All rights reserved. |

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3